Ten years ago, historian and activist Ines Rieder died unexpectedly in the early hours of December 24. We remember our comrade-in-arms and republish the obituary from 2015. A remembrance by Andreas Brunner

Ten years ago, historian and activist Ines Rieder died unexpectedly in the early hours of December 24. We remember our comrade-in-arms and republish the obituary from 2015. A remembrance by Andreas Brunner

Just a few weeks ago, we sat together and chatted about current projects and plans for the new year. Ines wanted to finish her biography of Mopsa Sternheim, which she had been working on for years and in which she had invested so much heart and soul. And then there would certainly be many other projects that excited her curiosity, because Ines was first and foremost curious. Curious to follow new leads in researching the history of lesbians and gays, but also curious about life, being together with people, conversations and, yes, arguments. Because Ines was also quite contentious when it came to exploitation, injustice and the rights of the weak.

I got to know Ines around the mid-1990s, after she had returned from the USA and chosen Vienna as the center of her life again, although she always remained a citizen of the world, commuting between Brazil, the USA and Europe. During this time, Ines became involved in the ÖLSF, the Austrian Lesbian and Gay Forum, and contributed her experiences from the American movement to the fight for equal rights in this country. Born in Vienna in 1954, her education at the Caritas Vienna training school for higher social professions and a degree in political science and ethnology at the University of Vienna awakened her spirit for a lifelong commitment to social issues, the fight for equal rights for women and the international lesbian and gay movement. In 1976, Ines moved to the USA, where she worked in California as a journalist and translator for the People’s Translation Service collective, co-editing the magazines Newsfront International and Connexion. An International Feminist Quarterly worked. After a stay in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Ines Rieder worked in California for Cleis Press, today the largest independent queer publishing house in the USA, where she and Patricia Ruppelt published the world’s first book on women and AIDS in 1988 under the title AIDS: The Women. Frauen sprechen über Aids, the German translation of which was published by Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag in 1991, was also the first comprehensive German-language publication on this subject.

Ines, who soon devoted herself entirely to her writing projects, had mixed feelings about the initiatives of the lesbian and gay movement for recognition of their partnerships and the fight to open up marriage to same-sex couples. Her feminist stance made her suspicious of these bourgeois instruments, and she questioned them as ingratiation with capitalism, which continued to advance despite global crises, in the guise of neoliberal economic ideologies. Although she came from a thoroughly middle-class background, Ines had an unmistakable sense of social injustice, fought against the overexploitation of the world’s resources and sometimes radically refused to consume anything.

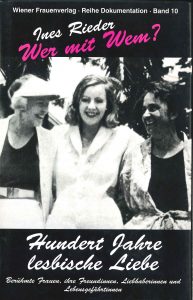

Her interest in the buried and concealed history of lesbians resulted in 1994 in Who with whom? One hundred years of lesbian love, her first major historical publication, which later also appeared in paperback. It focused on networks of lesbian women in Berlin, Paris, London and New York. Viennese stories will only be found in passing in this volume, and little was known about them in the 1990s. Ines Rieder deserves credit for her meticulous research into the sources. Once she had found a lead, she followed it up in archives, working her way through estates, collections of letters and diaries or criminal files. Ines Rieder was one of those historians who dealt with historical sources and, starting from a micro-history, placed them in a larger context.

Her interest in the buried and concealed history of lesbians resulted in 1994 in Who with whom? One hundred years of lesbian love, her first major historical publication, which later also appeared in paperback. It focused on networks of lesbian women in Berlin, Paris, London and New York. Viennese stories will only be found in passing in this volume, and little was known about them in the 1990s. Ines Rieder deserves credit for her meticulous research into the sources. Once she had found a lead, she followed it up in archives, working her way through estates, collections of letters and diaries or criminal files. Ines Rieder was one of those historians who dealt with historical sources and, starting from a micro-history, placed them in a larger context.

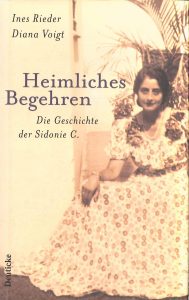

Together with Diana Voigt, Ines Rieder published a biography of the lesbian Freud patient Margarete Csonka-Trautenegg in 2000, which was also a biography of the 20th century. Gretl, as Ines and Diana affectionately called the old lady with whom they had conversations for years, was born in 1900 and died at the age of 100 in the year her biography was published. Her life reflected the century, her youth in the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Monarchy, her aborted analysis with Freud, which he nevertheless processed into his only essay on female homosexuality, finally her escape from persecution as a “Jew” by the National Socialists and her exile in Cuba and the USA. With empathy and great expertise, Ines Rieder and Diana Voigt embedded this life story of a woman who refused to deny her desire despite social ostracism in the larger context of history.

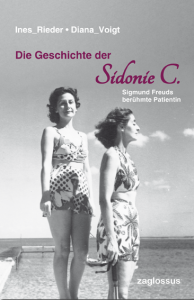

Now almost a classic, Gretl’s biography is available in a new edition – with an afterword by Ines Rieder – under the title Die Geschichte der Sidonie C. from Zaglossus Verlag. It was translated into several languages (French, Spanish and Portuguese) and sparked heated discussions, especially among French psychoanalysts, as shown by contributions at symposia and conferences to which Ines was invited several times. As a freelance journalist, author and historian, Ines Rieder has been involved in two important projects for the LGBT community in Austria: in 2001, she was co-editor of The other view. LesBiGay life in Austria the catalog for an exhibition that could not take place. In the year of Europride in Vienna, a group of cultural historians wanted to hold the first major exhibition on lesbians, gays and trans people in Austria at the Vienna Museum, but failed due to the sustained resistance of the director at the time, which is why “only” a catalog was published.

Four years later, the time had come: at the exhibition secret:life. gays and lesbians in 20th century vienna which took place in an industrial hall in Neustiftgasse in the fall/winter of 2005/2006. For the largest exhibition on Vienna’s LGBT history to date, with over 700 objects from all over the world, Ines, as co-curator, was able to draw on her extensive historical knowledge as well as her wide-ranging contacts. For the exhibition, she dug up forgotten artists (such as Helene von Taussig or Helene Funke) and inspired young ones (such as Sigrid Hutter) to create new works, she paid tribute to musicians Ethel Smyth or Smaragda Berg, who had also been neglected by history, and delved into scandalous affairs of the wild 1920s in Vienna. She devoted herself in detail to a lesbian/gay group at the Viennese Volkstheater in the early 1930s, which included illustrious names such as Christa Winsloe and Lina Loos, but also those known only to connoisseurs today, such as Margarete Köppke or Sybille Binder – and the gay Egon von Jordan. What interested her in history – the reconstruction of lesbian or gay/lesbian networks – she also lived as a convinced networker herself.

Four years later, the time had come: at the exhibition secret:life. gays and lesbians in 20th century vienna which took place in an industrial hall in Neustiftgasse in the fall/winter of 2005/2006. For the largest exhibition on Vienna’s LGBT history to date, with over 700 objects from all over the world, Ines, as co-curator, was able to draw on her extensive historical knowledge as well as her wide-ranging contacts. For the exhibition, she dug up forgotten artists (such as Helene von Taussig or Helene Funke) and inspired young ones (such as Sigrid Hutter) to create new works, she paid tribute to musicians Ethel Smyth or Smaragda Berg, who had also been neglected by history, and delved into scandalous affairs of the wild 1920s in Vienna. She devoted herself in detail to a lesbian/gay group at the Viennese Volkstheater in the early 1930s, which included illustrious names such as Christa Winsloe and Lina Loos, but also those known only to connoisseurs today, such as Margarete Köppke or Sybille Binder – and the gay Egon von Jordan. What interested her in history – the reconstruction of lesbian or gay/lesbian networks – she also lived as a convinced networker herself.

As such, it docked with QWIEN as a matter of course. Even if we didn’t always agree on all issues, we pulled in the same direction. Our shared interest in researching and preserving Vienna’s lesbian/gay history in an archive accessible to all strengthened the bond. In collaboration with QWIEN, she presented a lecture on Dorothea Neff, who hid her “Jewish” partner Lilly Wolff as a submarine during the Nazi era and thus saved her life. Ines took her story as an opportunity to fundamentally address the issue of lesbian submarines in the Nazi era, which had never been dealt with in research before, and to search for further cases in extensive file research in the Vienna City and Provincial Archives. On the basis of file material, she also reconstructed previously unknown details about lesbian life in the 1950s and published an essay on the subject in the historical journal Invertito.

Her enthusiasm for history should also spread to young historians, which is why she gladly accepted invitations to give lectures and workshops, for example at the first Queer History Day or at the conference on the question of a memorial for the homosexual and transsexual victims of Nazi persecution (both in 2014). One of her last major publications appeared in the catalog for the exhibition Dance of the Hands at the Photoinstitut Bonartes and dealt with the dancers Tilly Losch and Hedy Pfundmayr, who were celebrated in Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s.

Her enthusiasm for history should also spread to young historians, which is why she gladly accepted invitations to give lectures and workshops, for example at the first Queer History Day or at the conference on the question of a memorial for the homosexual and transsexual victims of Nazi persecution (both in 2014). One of her last major publications appeared in the catalog for the exhibition Dance of the Hands at the Photoinstitut Bonartes and dealt with the dancers Tilly Losch and Hedy Pfundmayr, who were celebrated in Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s.

Ines was a great storyteller and a historian who was happy to share her knowledge. She was open and welcoming to students’ requests and provided material. How often I called her when I needed another lesbian story for my city walks. I could be sure that Ines would conjure up a biography from her historical treasure chest that had not yet been adequately told. Her historical expertise was in demand, including for the documentary “Warm Feelings”, which was broadcast by ORF in May 2012. In recent years, she has had a particular soft spot for individual members of the Mann family – especially the siblings Erika and Klaus – and their global network of work and relationships, which also included Mopsa Sternheim. She could certainly have told us as much about this as she did about other stories that she tirelessly researched.

Ines Rieder’s voice fell silent all too soon on 24 December. But her stories will remain.

A group page on Facebook commemorates Ines Rieder: https://www.facebook.com/groups/inesriedermemorial/

Excerpts from an interview for the QWIEN project Stonewall in Vienna (2009): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zfaMFiED1JA

Selected bibliography:

Ines Rieder/Patricia Ruppelt (Ed.): AIDS: The Women. San Francisco 1988 (together with)

Ines Rieder/Patricia Ruppelt (eds.): Women talk about AIDS. Frankfurt 1991

Ines Rieder: Feminism and Eastern Europe. Cork 1991

Ines Rieder: Wer mit Wem? Vienna 1994; paperback edition: Munich 1997

Ines Rieder: Wer mit Wem? Vienna 1994; paperback edition: Munich 1997

Ines Rieder/Diana Voigt: Heimliches Begehren: Das Leben der Sidonie C., Vienna 2000; paperback edition: Reinbek 2003

Wolfgang Förster/Tobias G. Natter/Ines Rieder (eds.): The Other View. Lesbian-gay life in Austria. Vienna 2001

Andreas Brunner/Ines Rieder/Nadja Schefzig/Hannes Sulzenbacher/Niko Wahl: geheimsache:leben. schwule und lesben im wien des 20. jahrhunderts (exhibition catalog). Vienna 2005

Paola Guazzo/Ines Rieder/Vincenza Scuderi (eds.): R/esistenze lesbiche nell’ Europa nazifascista.Verona 2010

Ines Rieder/Diana Voigt: Die Geschichte der Sidonie C. Sigmund Freud’s berühmte Patientin. Vienna 2014 (new edition of Secret Desire)

Contributions in (selection):

Ines Rieder: The story of an infectious passion. In: Sigrid Hutter: 100 women. Feldkirch 2010

Ines Rieder: Lesbische und lesbotextuale Einblicke. In: Maria Froihofer/Elke Muröasits/Eva Taxacher (eds.): l[i]eben und Begehren zwischen Geschlecht und Identität (catalog for an exhibition at the Joanneum Graz, 2010). Vienna 2010

Ines Rieder: On tour. Lesbischwules Kommen und Gehen in Österreich zu Zeiten des § 129. In: ÖGL – Österreich in Geschichte und Literatur mit Geographie, 2010, 54. Jg, Heft 3

Ines Rieder: On tour. Lesbischwules Kommen und Gehen in Österreich zu Zeiten des § 129. In: ÖGL – Österreich in Geschichte und Literatur mit Geographie, 2010, 54. Jg, Heft 3

Ines Rieder: Aktenlesen 1946-1959. Lesbians in Vienna im Visier der Justiz. In: Invertito. Jahrbuch für die Geschichte der Homosexualitäten, 2013, vol. 15

Ines Rieder: Lesben lassen Hände sprechen. In: Monika Faber/Magdalena Vuković (eds.): Dance of the hands. Tilly Losch and Hedy Pfundmayr in Photographs 1020-1935 (catalog for an exhibition at the Photoinstitut Bonartes). Vienna 2013

Historical advice:

Warm feelings. Four love stories from Austria. A film by Katharina Miko and Raphael Frick (A 2012)